For the first time since 2002 the World Press Freedom Index (WPFI) has classified the global state of press freedom as a “difficult situation”, in 2025. This situation has been compounded by economic pressure, where “news media are caught between preserving their editorial independence and ensuring their economic survival.”

The Index, released by RSF (Reporters Without Borders) every year, looks at the state of press freedom in 180 countries. This year, the report found that in 160 countries, media outlets achieve financial stability “with difficulty” — or “not at all.”

RSF in its WPFI last year had stated that “press freedom around the world is being threatened by the very people who should be its guarantors – political authorities. … of the five indicators used to compile the ranking, it is the political indicator that has fallen most…”

This year however, the worst hit was taken by the economic indicator, leading to shutting down of media outlets in around one-third of countries, globally.

Along with economic stress, censorship, violence against journalists, imprisonment and assassinations of journalists, manipulation of information are all pressures that still weigh on press freedom.

Access to critical information is becoming more restricted by the day as governments across the world, even in democratic countries, limit freedom of expression and come down hard upon media outlets publishing exposées and other stories critical of the government.

But journalists and media support organizations are finding creative ways to get around the barriers of direct and indirect censorship going up around the globe, including democratic countries that need a free press to help individuals make informed decisions.

RSF’s Uncensored Library (UL) is one such way to get access to restricted articles in countries where citizens are only being served government-backed propaganda in the name of news. And denying them access to the reporting critical to the systems of power.

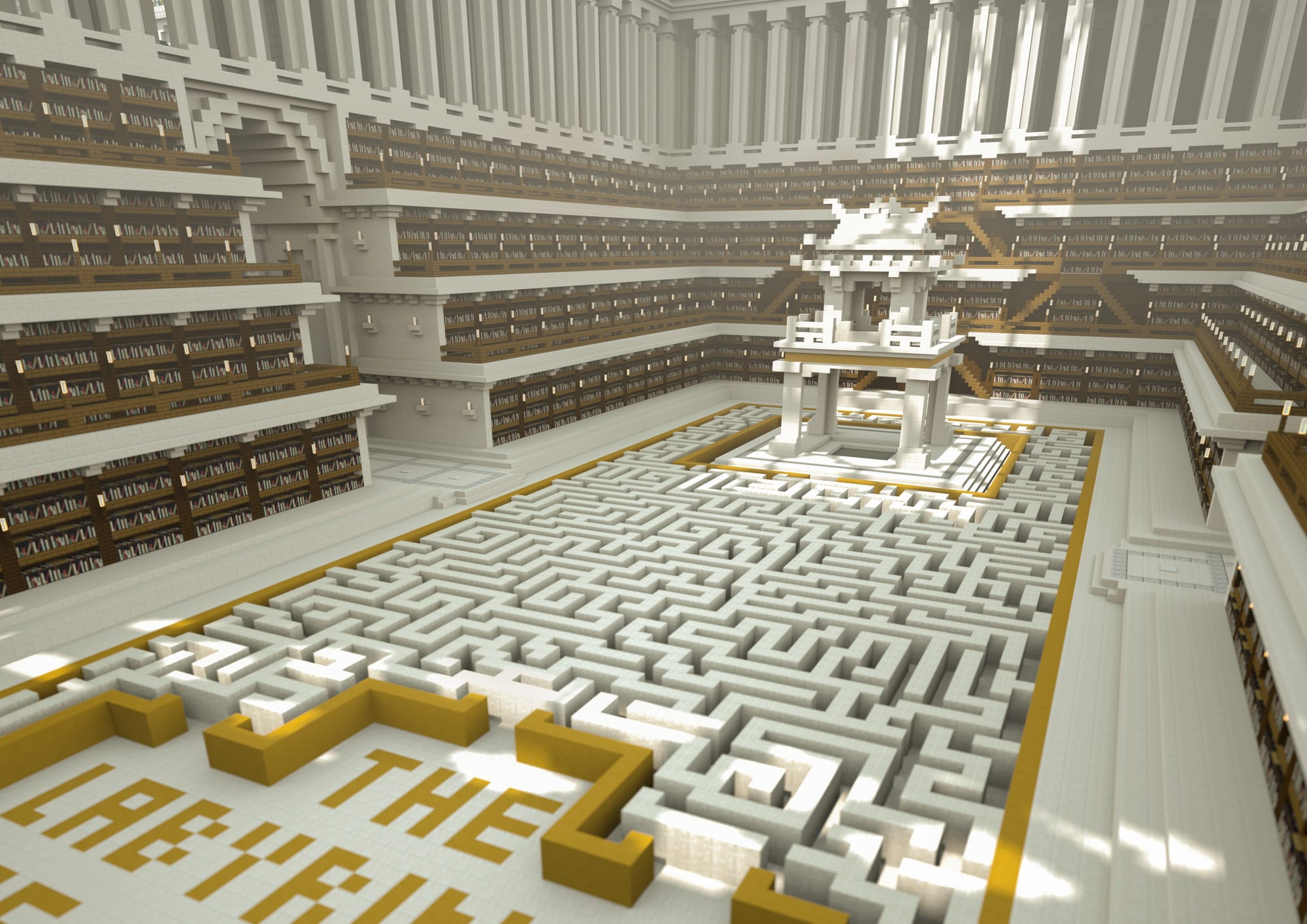

The UL — a collection of articles from journalists in exile or those working from hideouts, and sometimes even those killed in the pursuit of truth — is an Easter egg inside the popular online game of Minecraft.

The idea was to keep journalism alive by using a loophole. Even in countries where almost all media is blocked or controlled, the computer game — Minecraft — is still accessible. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) uses this loophole to bypass internet censorship and makes some censored articles available to the readers in the form of books inside the game.

UL was launched on the World Day Against Cyber Censorship — March 12, 2020. In the 5 years since its inception, it has allowed citizens of many countries to read news that their governments want to keep from them, with the help of an online game.

The online library comprises 300 books featuring articles from journalists working to keep journalism alive even in the most oppressed nations.

Walking ION through the concept of the UL in more detail, Sibylle Loock of the UL said, “The UL publishes journalistic texts selected by our organization, Reporters Without Borders. These texts were written by journalists or published by media outlets that have taken great risks in their work. Some of the authors represented in the UL have been imprisoned or even murdered because of their articles.”

Sibylle explained that the texts included in the UL were deliberately chosen not to cover current affairs but to provide an analysis of the country’s situation in a way that remains as timeless as possible.

“Selecting the texts is a lengthy process, as we must obtain permission from media outlets, authors, or their relatives (in the case of journalists who have been killed) to use their articles. As a result, the content is not updated daily,” she added.

When the UL was launched five years back, it included articles by journalists from Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Mexico, and Vietnam. Speaking about the selection process, Sibylle said that the team focuses on the level of activity within a country’s Minecraft community, and the severity of press freedom violations in that country.

“The World Press Freedom Index, which we publish annually in May, plays an essential role in identifying where independent journalism is most at risk and where access to uncensored information is urgently needed. The final decisions are made in close coordination with our headquarters in Paris,” she explained.

Gaming for reach

The UL was built inside the online game but its reach extends far beyond gamers now, resonating with global audiences interested in knowing more about press freedom and what governments are gatekeeping.

According to Sibylle, in 2024, the UL project website attracted around 200,000 visitors with the largest audiences coming from the USA and Germany, followed by India, Russia, Brazil, and Mexico.

The Minecraft map, which allows users to explore the library offline, was downloaded approximately 80,000 times in 2024. Additionally, their offline Minecraft map — where the library can be downloaded — recorded 39,000 visits and over 336,500 texts read. Users, who have bought the game’s subscription, can share this version to help make access more resilient and harder to censor.

Because of its nature — challenging censorship in a unique way — the UL has been featured in media outlets and also on social media handles, expanding its reach with every story that goes viral.

“We frequently receive inquiries from journalists and university scholars, highlighting the project's relevance,” she said.

While it is creative and bold, the team behind the UL is highly aware of the challenges they face and those they might encounter in the future.

She says while this is a solution they have found to provide access to restricted articles in certain countries, it would be great if the UL could serve as a “sustainable, long-term solution to censorship”. But that is not their goal.

“Our ultimate goal is to eliminate the need for such projects altogether. We advocate for a world where journalists can do their jobs freely and safely—without fear, restrictions, or the need for alternative platforms,” she said.

Having said that, she added that if the day comes when the UL is no longer sustainable or if the project is taken down, or if Minecraft is banned in these countries, they have thought of more creative alternatives.

“Before the UL, we launched the Uncensored Playlist, a campaign that transformed censored journalistic articles into pop songs, making them accessible via global music streaming platforms. Its success demonstrated that innovative formats can help bypass censorship,” she said.

Running a project of this cadre requires resources — both human and financial. However, there is no revenue model behind the UL. The advertising agency DDB developed and built the library pro bono, and the team continues to maintain it with the help of a former DDB employee who now supports the project voluntarily.

“As for the journalists whose work is featured, the articles included in the library were originally published in established media outlets. We chose them because they are often censored or difficult to access in the authors' home countries,” added Sibylle.

Why do we need creative ways to bypass censorship?

The UL began with five countries - Vietnam, Saudi Arabia, Mexico and Egypt but the list of countries and journalists featured on the UL seems to be growing. The UL expanded to include articles from Brazil, Belarus, Eritrea, in 2021 and then to Iran and Russia in 2023, bringing up the total number of countries featured on its platform to 13.

“Less than 1% of the world’s population lives in a country where press freedom is fully guaranteed,” according to Fiona O'Brien, UK director of RSF.

Even in democracies, where freedom of speech is protected, press freedom cannot be taken for granted. If you consider the world’s most populated democracies, India and the U.S., conditions for journalism have continued to deteriorate.

Journalists working in these countries face constant pressures that challenge their independence through economic and political factors. Making it imperative to not just engage with, but work towards creative approaches like the UL that bypass press censorship.

After coming back to power, President Donald Trump has issued several executive orders, making life difficult for many sections of the society, journalists being one of them. Currently, the USA ranked 57th on RSF’s 2025 Press Freedom Index, falling down two places from 2024.

The USA was reported to be in a “problematic situation” when it came to freedom of press in 2024, but the rankings might tank further if the current situation continues.

Meanwhile, India continues to be in the lowest category — where situations for press freedom are considered “very serious” — since 2023. With over 900 private channels, ranked 159 of 180 in RSF’s Press Freedom Index in 2024. While its ranking improved by eight positions in 2025, it still falls under the group of 42 countries with the worst press freedom along with countries like Russia, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, North Korea, Syria, Turkey and Myanmar to name a few.

Earlier in 2025, citing India’s falling ranks in RSF’s press-freedom index, a statement by DigiPUB — a platform that represents digital news media organisations in India — added that while large chunks of the mainstream media have become “governments cheerleaders”, it is these independent media outlets that are questioning the government and its policies, even when they are struggling to survive without government and commercial advertisements.

RSF’s new findings also share similar concerns that loss of advertising revenue and media ownership concentration “pose a serious threat to media plurality.”

“Meanwhile, the concentration of media ownership in the hands of influential groups linked to those in power — as seen in India (151st) — combined with growing economic pressures even in established democracies, means that press freedom in the region faces mounting repression and increasing uncertainty,” it stated.

India is listed in RSF’s press freedom index under “very serious situation”. This in itself is an alarming situation for the world’s largest democracy.

Venkatesh Nayak, Programme Head of the Access to Information Programme at Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative, working for the Right to Information and news transparency in South Asia, Africa & the Caribbean lamented the state of press freedom in India.

“It is unfortunate, but with the new Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules 2023, which came into force in April 2024, press freedom is gradually being eroded. In the guise of fact-checking, it is a tool to control the digital media and get anything anti-government off of the internet, terming it as ‘fake news’ or ‘misinformation’,” he said.

As conditions for practicing journalism get “difficult” or “very serious” in over half of the world’s countries, creative solutions may be needed to maintain the connection between journalists and the public. The UL offers one unique approach to begin tackling this challenge.

![5 years of gaming the [censorship] system[s]](/content/images/size/w1200/2025/05/rfs-wpfi-minecraft--1-.jpg)