The digital era has seen a rise in remote reporting as newsroom travel budgets are cut and staff sizes shrink. In some ways this has presented new opportunities — journalists can hop on a call with people almost anywhere in the world and find new contacts more easily than ever. They can cover stories from places they have never visited and collaborate with journalists they might never meet in person. But it also presents a challenge — especially in the video space. Because journalists now have to spend a lot of time digging for footage they can use in their video reports when they can’t go in the field. And this is happening at a time when more and more people are turning to social media videos to get their news.

For a long time, wire services have filled the footage gap. But they aren’t immune to the global decline in media business revenues. Also, these services can be expensive, so many newsrooms turn to open license footage on platforms like Wikimedia, Pexels, Pixabay and Flickr. Open license footage is footage that people can use freely. Sometimes it comes with conditions, like the need to credit the original creators, but often there aren’t many restrictions for others to reuse. Sites like Pexels and Pixabay can be great for finding footage for generalised news coverage and explainer videos. They don’t cut it for diverse representation of the world, though.

Over the last year, my team and I at InOldNews have been trying to figure out how to measure diversity and representation on these platforms to identify the gaps. And it doesn’t take more than a quick search to see that there is a big difference in what footage can be found from different parts of the world. There is much less footage available from South Asia than there is from North America. Even though South Asia is home to 25% of the world’s population, and North America is home to just 4.7%. A search for capital cities in many parts of the world will result in prompts saying “no results” or asking us to check our spelling.

We wanted to understand what this meant for journalists. And the Newmark J+ Entrepreneurial Journalism Creators Program (EJCP) gave us the perfect opportunity to explore this question.

When I started my journey at EJCP, I had a suspicion that creation of a more diverse pool of open licensed footage online could increase diversity and representation in video journalism. But I wanted a deeper understanding of this question. I also wanted to better understand the reasons why representation in the media is such a challenge in video journalism. I knew there would likely be many reasons, but I wanted to figure out which area to focus on first.

So, we launched a Creative Commons in Video Survey and got responses from video journalists in 14 countries.

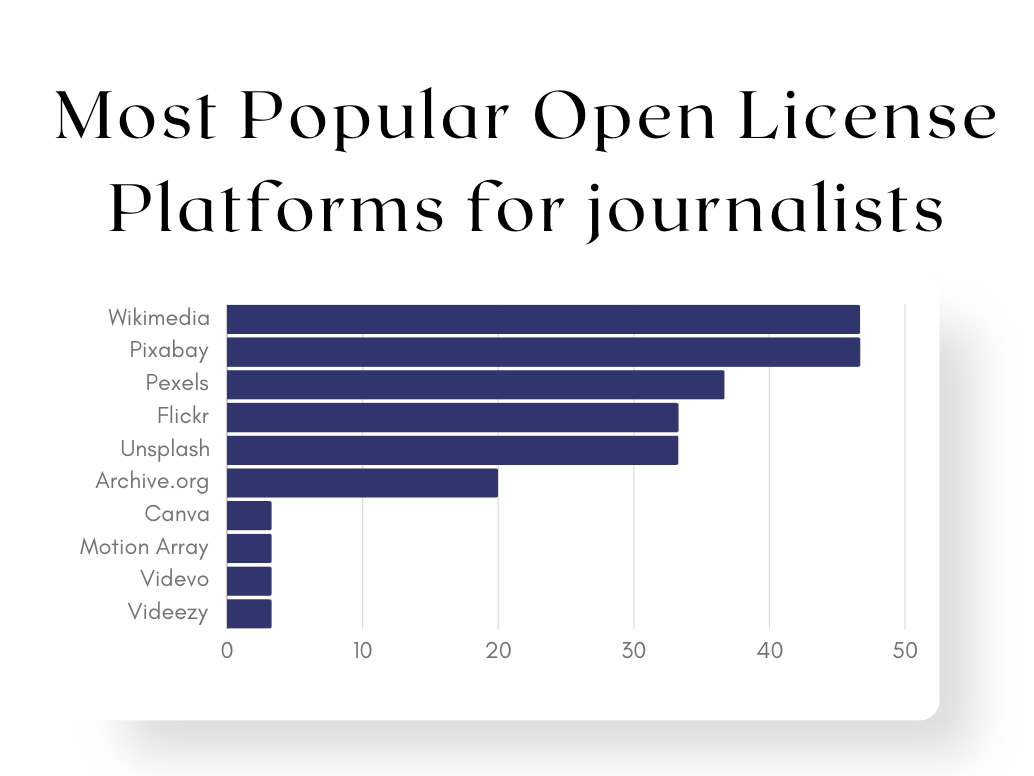

The first thing we wanted to understand was what platforms journalists used the most when looking for free footage. Wikimedia and Pixabay emerged as the most popular sites, followed by Pexels, Flickr and Unsplash.

Journalists indicated that they had a difficult time finding footage that was representative of where they come from on these websites. Others mentioned that understanding what rights they have to use the footage was a challenge sometimes.

“At times it is not too clear if the footage is genuinely under [a Creative Commons license] since I have found licensed photos under CC by mistake, especially on Flickr,” one respondent told us.

Another shared, “When I want to tell a story, I aim to use relevant images or footage in my video. However, most of the time, we end up using generic footage, which doesn’t enhance but rather diminishes the quality of my video”

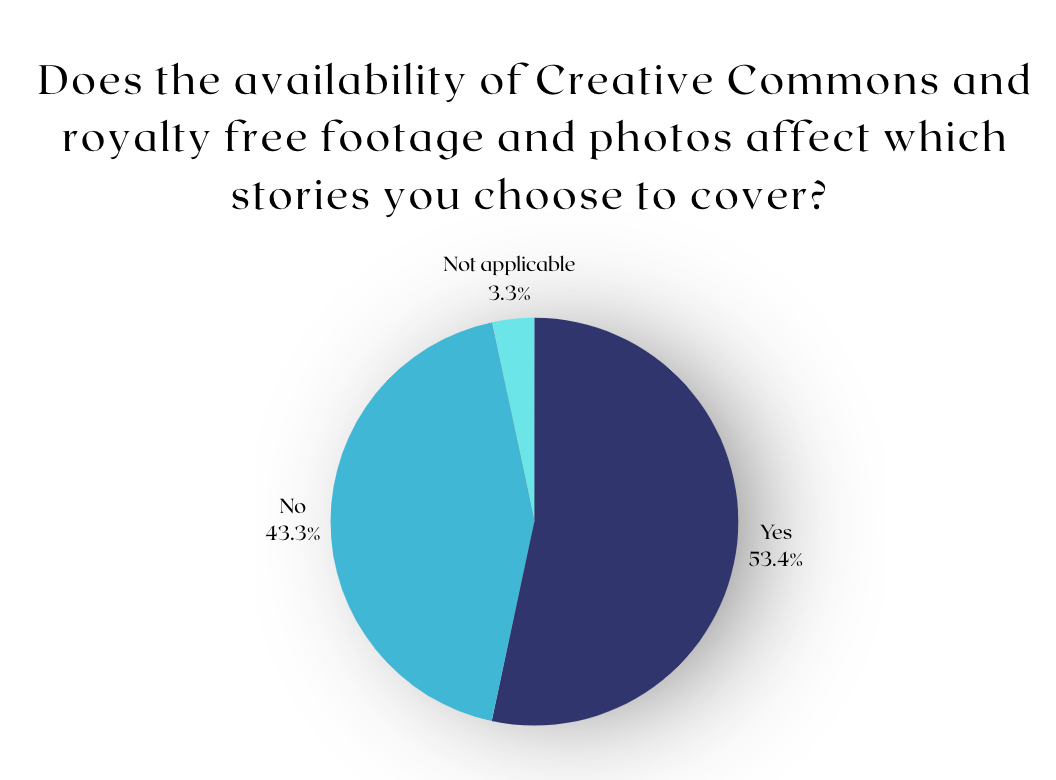

All of these challenges can influence whether journalists choose to tell a particular story, we found. In fact, more than 50% of the respondents indicated that what footage they find affects what stories they tell.

So can AI help fill these gaps? Our survey results indicate that 80% of journalists aren’t turning to AI when they can’t find footage. And this could be for a variety of reasons, but our suspicion is that it’s largely because AI isn’t good at creating the kinds of accurate footage journalists need. Reporting by Rest of World found that AI often produces stereotypical images of people from India, Nigeria and many other countries. The results were also replicated by the Washington Post a few weeks apart.

Journalists also largely don’t feel like there’s much they can do to fill these gaps. More than 80% of survey respondents said they don’t upload their own footage to these sites, and the reasons they listed were mostly linked to a lack of time, and resistance from the newsrooms they work in. Many indicated they hadn’t even considered uploading their footage before or didn’t know it was an option. I hadn’t either until a few years ago, even though I had been using free footage and photos for my stories for a decade now.

We’re going to keep this survey open so we can continue to gather data as one of the ways to gauge the state of open journalism. But in the meantime, we’re also moving forward on our efforts to address the gaps in footage. In the last year and a half we’ve uploaded more than 200 clips to Pexels, Pixabay and Flickr. It’s just a start, and we have a long way to go. But the results so far are encouraging. Till date, the footage has been downloaded more than 25,800 times, and viewed more than 1.9 million times. And those numbers grow every day. We often get more than 50 downloads a day.

All of this research and uploading of footage is helping with our next steps, which are focused on raising funds so that we can expand our efforts. We want to commission journalists to document their own communities, because they’re the real experts. They have a keen understanding of what is important to their community, and where there are gaps in reporting. I shared some details about what our next steps are in this presentation for my EJCP cohort:

We also have plans to build our own platform that will provide editorially driven, open-licensed, free to use footage. Because our experience with existing platforms is that they’re not very practical for journalistic purposes. Our survey results indicated this too. So a new platform is the long term goal, but as we build towards that we’re going to keep chipping away, clip by clip, at filling in some of the gaps we see in free footage online.

Being part of EJCP has helped me find answers to some very important questions I had at the start of the program. It’s helped us build a road map and the confidence to ask more ambitious questions. Like is this a limited project, or is this a movement? I’m excited to find out. And you can join us on this journey. To get in touch, email editor [at] inoldnews.com.