This week we’re bringing you an excerpt from a personal essay published by our friends over at Unbias The News. Click here to read the full article.

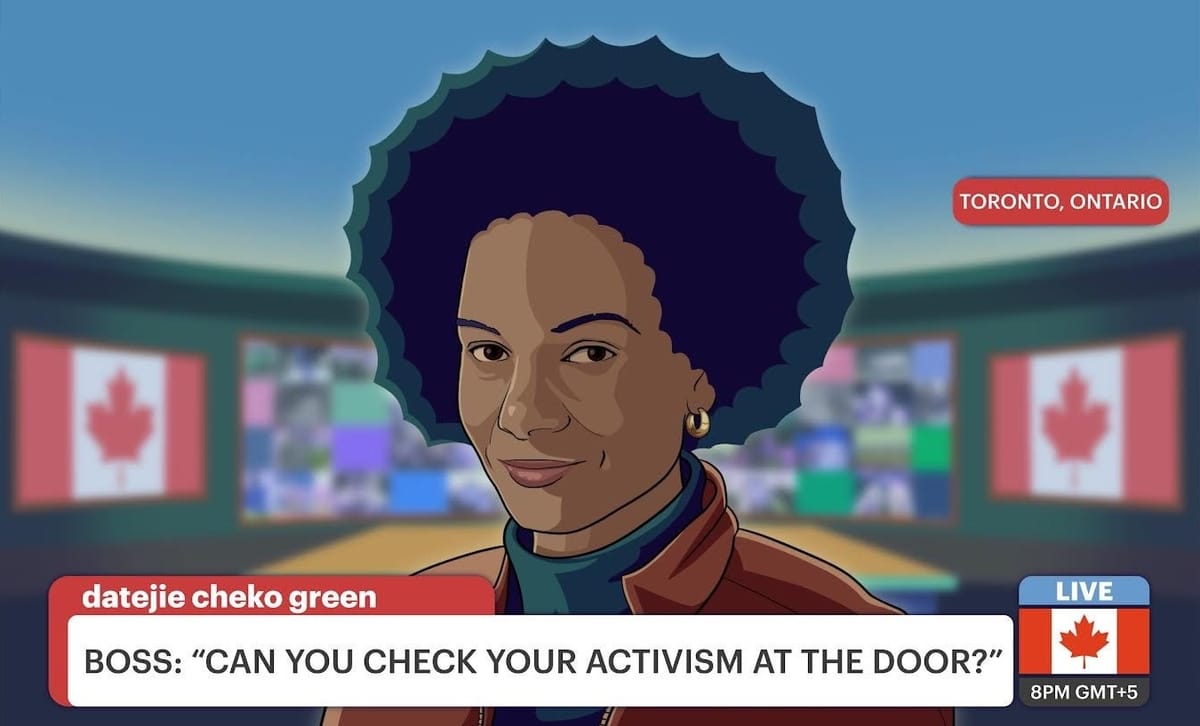

Can you check your activism at the door? Under white supremacy, Black Canadian journalists see their very existence as a radical act

Written by datejie cheko green, Edited by Wafaa Albadry, Illustration by Walker Gawande

Originally published: 7 December 2021“Can you check your activism at the door?”

This was how my white boss-to-be seemed to sum up my candidacy for a journalism position at the Canadian public broadcaster CBC in the 2000s. It came at the end of three long and very unofficial one-on-one hiring interviews.

I was thirty-something, a Jamaican-Canadian born and raised in rural Ontario, presenting with public-interest radio experience, a university degree, and a professional audio production diploma, both with honors. I’d lived abroad and was bilingual in English and French. I was a dozen years urbanized in Toronto’s vibrant, multilingual and multiracial communities.

I had little activist experience, unless people define “activism” as living in one’s own skin and saying no to the racism, sexism, homophobia and other discrimination we experience.

Even though discriminatory practices exist in Canada and are not acceptable under Canadian laws, I did not discuss them in my resume or during the hiring process.

For each job interview where it would have been normal to pitch one or two news story ideas, they required me to pitch dozens, including guest names and details for “adding diversity” to the public broadcaster’s flagship radio program. My pitches were very well received, but at the end of the recruitment process, my boss went back to my resume and questioned my Black-specific professional experiences, one by one.

“Why did you study for a year in Cameroon in 1990?” they asked me, quizzically.

“Why did you volunteer at an after-school program for Black children in 1993? And why in Scarborough?”

The program ran in a part of the city resettled by immigrants from the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia. It was one of many local education projects that Black people have historically created so their children can learn in culturally safe and affirming environments. Their decades of organizing later resulted in the establishment of the Africentric Alternative School in Toronto in 2009.

I knew about Black children’s needs and their parents’ innovative solutions, but these were being held against me in this arena of a journalism interview. Behind the way my boss appraised my appearance, their eyes up and down my body, I expected the next question to ask about my locked natural hair. But what came was worse.

“Can you check your activism at the door?”

I paused, and calmly replied, “I am a professional.”

The next day I was hired.

Practicing Journalism While Black

The disproportionate scrutiny of my Black-centred choices was the first sign of the anti-Black-journalist distrust at the heart of Canada’s white-centred news industry. This treatment groomed me for their race surveillance of my professionalism before my job even began, and would reveal itself in the day-to-day micro-decisions of the newsroom.

In my dual role as studio director and story producer, I was directed to clean up the run of the program’s nightly live broadcast. I quickly succeeded, to the relief of the hosts and crew, and to praise from executives across the country who commended my boss, who then told me. Proof of my value, I thought, hopefully.

My other role was to produce interviews for daily broadcast selected in the morning story meeting, the most powerful newsroom ritual that feeds the editorial process.

Newsmaking revolves around this daily meeting to determine what is news, who is the audience, and the task assignment for who gets to produce which stories.

On our show, the meeting also functioned as an elimination round, evaluating each producer’s journalistic and “other value” to the program. This culture actively encouraged us to take comfort in the elimination of our peer’s stories as we advanced our own, and, therefore advanced ourselves. Most of my white colleagues embraced this. I couldn’t relate.

Out of a dozen on our team, I was usually the only Black person, intermittently one of two racialized people. As requested, each morning I pitched stories that addressed Canada’s racialized and marginalized communities, members of the same public whose tax dollars paid us all as journalists, though we were coached to visualize a ‘farmer in Saskatoon,’ a white man in the prairies, as our target audience’s persona, and his presumed interests formed our backdrop.

All at one time, I saw how journalistic practices created Black underrepresentation: as journalists, in news stories, and as audiences too.

Read the rest of the story on Unbias The News.

You can also join Hostwire, where members get alerts about trainings and journalism opportunities in general.

Thanks for reading, and we’ll be back in your inbox soon!